A couple of years back, I had posted something on creating complex yet recallable passwords by transposing letter shapes on the standard available keyboard. We will continue along those lines, in the timeless manner of using language alone to build individually understandable complexity, which is a delicate balance of chaos and order. Language in itself is ordered complexity, but its rules can be flouted, as like how a child would and chaos be quickly created. Your mental space resides somewhere in that region.

The most frequently used passwords, which are typed in every day ritualistically, quickly become entrenched in one’s muscle memory. This becomes apparent when one returns to the machine after a long break, or while trying it on a different equipment, or when the UI or the workflow to typing in that password has changed ever so slightly. But, it is quick to recall the orchestration of one’s fingers, and even override the old pattern with a few practise runs. This is the first thing one might do for frequently used passwords, even before referring to the hint or other recall methods.

But when that doesn’t work, hints are used – these can be straightforward mentions of what the password is, or are equally cryptic. Usually these strings are only apparent to the users themselves, or a small number of people. Even in this case, one’s ability to recall the details is crucial, and this bit often fails.

Using Native Language

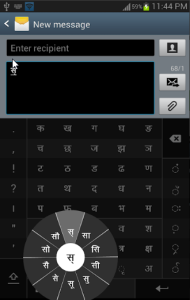

For bilingual people, and especially for people familiar with different scripts, new avenues of creating and remembering passwords open up. As you go about your life, you are encrypting and decrypting information in the languages you know, a non-stop process of mental transliteration and translation to the language you think in.

Let us assume that the password or hint string is ‘121212’. Here is how someone who knows both Hindi and English can recall this string:

Legible to English Speaker:

Onetwoonetwoonetwo, twelvetwelvetwelve…

Vntoovntoovntoo, twlvtwlvtwlv….

Legible to Hindi Speaker:

एकदोएकदोएकदो, बारहबारहबारह…

Legible to Bilingual person:

Hindi in Latin: baarahjanvarybaarah, baarahbaarahbaarah, ekdoekdoekdo, eksauikkisdosaubaarah..

English in Devanagari: वनटूवनटूवनटू, ट्वेल्वट्वेल्वट्वेल्व, वनट्वेन्टीवनटूट्वेल्व..

Hindi in Latin as a hint: raajakajanmdin, saalgirah, duniyakaannt..

English in Devanagari as a hint: दकिंग्ज़बर्थडे, एनिवर्सरी, डूम्सडे..

For shorter strings – like 2j2, the letters used to spell its characters themselves (teedabluohjeteedabluoh) could be transliterated to: टीडब्लिऊओजेटीडब्लिऊओ

Hieroglyph on your tongue

As obscure tongues have always been used by inner circles to maintain knowledge and secrets, we will explore another such layer of complexity with ancient languages. These languages continue to live in modern languages and yet they are considered dead. Since we are using Devanagari and Latin scripts here in the examples, let us introduce Sanskrit which lets us harness the power of long compound words and well defined conjunction and word joining sound rules. We can combine any word with another (while disregarding grammar). We can even transliterate English terms and compound them with other words as if they were Sanskrit. The examples here might be absurd, but they are only bound by the limits of absurdity of their creator’s inner monologue.

news speed light city -> वार्ता त्वरा प्रकाश नगर -> वार्तात्वराप्रकाशनगर -> vaartatvaraaprakaashnagar

fast typing friend -> तरस्वत् लेखः मित्रम् -> तरस्वल्लेखोमित्रम् -> tarasvallekhomitram

These are not foolproof solutions and have their own vulnerabilities – anyone who recognizes the scripts and has an internet connection could crack these without even knowing the languages. But, this method does help in obtaining strings which are probably do not exist in a dictionary. Because the Latin script is limited in capturing the correct pronunciation on regular keyboards, and because people transliterate the same word differently, writing these without space helps make them more confusing except to the person who has created these strings.

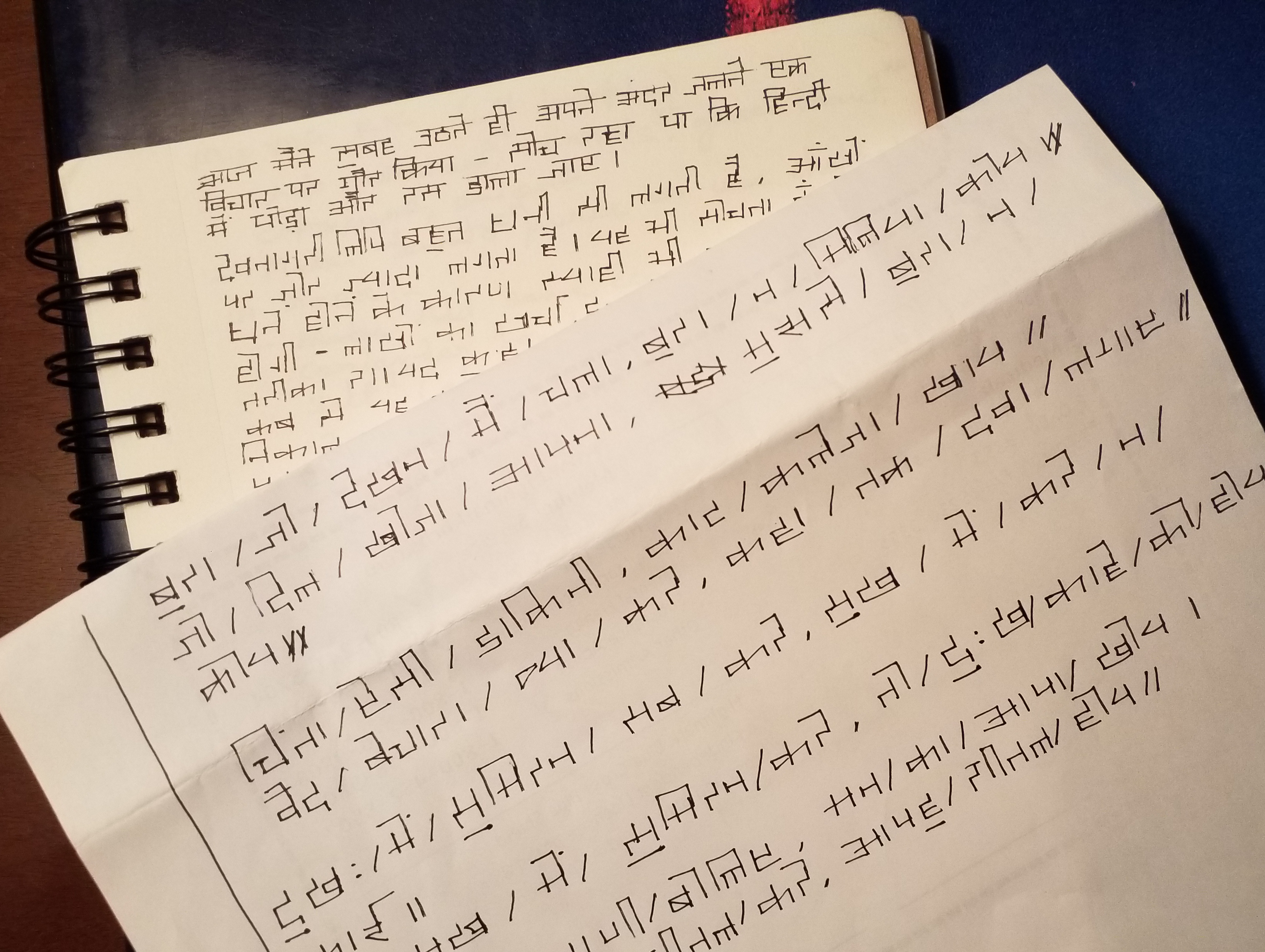

This process, thus, can be layered within a stack of other obfuscation methods. You can create a phrase, translate it to Sanskrit, and transliterate the sentence back. Utilizing physical media and strategies related to the medium will definitely help in making this effective.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanskrit_compound

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sandh

https://learnsanskritlanguage.com/grammar/starting-out/making-words/compound-words/

https://openpathshala.com/sandhi-in-sanskrit

https://learnsanskrit.org/start/nouns/sandhi/

https://greenmesg.org/sanskrit_online_tools/sanskrit_sandhi_tool.php

https://www.learnsanskrit.cc/index.php?mode=3&direct=au&script=hk&tran_input=city

![2020-05-04 19_39_57-(1) Blade Runner 2049 - Chinatown Scene [HD] - YouTube 2020-05-04 19_39_57-(1) Blade Runner 2049 - Chinatown Scene [HD] - YouTube](https://rotixchyavanprash.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/2020-05-04-19_39_57-1-blade-runner-2049-chinatown-scene-hd-youtube-e1588641403296.png?w=174&resize=174%2C153#038;h=153)

![2020-05-04 19_38_45-(1) Blade Runner 2049 - Chinatown Scene [HD] - YouTube 2020-05-04 19_38_45-(1) Blade Runner 2049 - Chinatown Scene [HD] - YouTube](https://rotixchyavanprash.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/2020-05-04-19_38_45-1-blade-runner-2049-chinatown-scene-hd-youtube-e1588641372463.png?w=174&resize=174%2C143#038;h=143)